When I studied history at school I was introduced to the concept of sources. There were exactly three types:

Primary Source

“An artifact, document, diary, manuscript, autobiography, recording, or any other source of information that was created at the time under study. It serves as an original source of information about the topic.”

Primary source, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primary_source, accessed 23rd August 2020.

Secondary Source

“A document or recording that relates or discusses information originally presented elsewhere.”

Secondary source, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secondary_source, accessed 23rd August 2020.

Tertiary Source

“An index or textual consolidation of primary and secondary sources.”

Tertiary source, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tertiary_source, accessed 23rd August 2020.

I forget the exact wording used by my teachers, but the versions above from Wikipedia are close enough to how I remember them.

But when I think about sources in genealogy, the definitions I learned in school history lessons are of limited use. As family historians our preoccupation is with the reliability of the information we find in sources and how it relates to our research question.

Just one source – a birth, marriage or death certificate, say, or a page from a census return – can hold multiple items of information about multiple individuals, contributed by multiple informants, each informant in possession of varying degrees of knowledge, memory or written reference, reported with varying degrees of honesty and exactitude, perhaps at an emotional moment in their lives (I have rarely been as nervous and emotional as my wedding day!). The reported information was captured on paper by a clerk, registrar or census enumerator who made best efforts to interpret the verbal or written submissions and record the outcome to the best of their ability, with handwriting of varying legibility. The resulting document is accessed by us, the researcher, as an original of possibly compromised condition, as an image of inadequate fidelity, as a transcript of perhaps uncertain quality or maybe as an index built upon a now difficult-to-access transcript or original.

Those single word descriptions, Primary, Secondary and Tertiary, seem inadequate to describe the detailed set of dependencies between the original submission of information and the possible outcome available to the modern researcher. They can barely help us at all in the all-important determination of reliability.

I’m not the first genealogist to think about this problem. One of my genealogical heroes, Elizabeth Shown Mills, has devised a more complex model for assessing genealogical sources, which she describes here: https://www.historicpathways.com/download/templateforee.pdf

ESM’s model is not straightforward, nor should it be – no system which aims to adequately interpret and classify the complexity of the sources that we rely upon can itself be trivial. Her colleagues in the Board for Certification of Genealogists in the USA have formally adopted her model. The version I describe in this article is the most up to date at time of writing and is described in the second edition of the BCG’s Genealogy Standards.

Sorting Sources

Under the new model, sources are considered as a container for information. Our first step is to assess the source. We consider the whole container, not the individual information elements within it, and think about what the original author intended. Was it:

- An original record

Intended by the author as a first recording of the information, regardless of whether this was at the time of the event or some time, perhaps years, afterwards.

Examples include:- Civil registrations of births, marriages and deaths captured at the original register office

- Parish registers and banns books

- Marriage licences and bonds

- 1911 census household schedules

- Wills and Administrations

- Military service records

- Apprenticeship indentures

- Passenger lists

- School registers

- Electoral registers

- Taxation records

- Court records

- Criminal records

- Naturalisation records

- Land and property transaction records

- Manorial rolls

- Contemporary photographs and portraits

- Gravestones

- A derivative record

A transmutation of an original record, whether that be an extract, an abstract, a transcription, a translation, an index, an image with hidden or modified information, etc. A derivative record must at some point have been based on an original record or a previous derivative of an original record, and we should always consider what the original record was thought to be. Note: even if the original record underpinning a derivative has been lost or damaged or is difficult to access, a derivative remains derivative!

Examples include:- All images of original records that lack sufficient fidelity or resolution, or that fail to show the whole page, or that fail to identify the location of the imaged page within the source, or that fail to show the rear face of an original document even if blank.

- Civil registrations of births, marriages and deaths copied to the General Register Office (transcribed from original registers)

- Bishop’s transcripts of parish registers (transcribed from original registers)

- All parish register indexes (including the whole of the IGI)

- Census enumeration books for the 1841-1901 censuses (transcribed from original household schedules, since destroyed)

- National probate calendars (abstracted from original wills and administrations)

- All memorial inscription transcriptions (by definition, transcribed from the original gravestones)

- Poll books (derived from electoral registers)

- Directories (trade, street, postal and telephone – published from compiled data which was often out of date)

- All translations from the original language

- All transcribed records on all genealogy sites!

- An authored or narrative work

Draws content chiefly from original and derivative records.

Examples include:- Obituaries

- All newspaper reports

- High school yearbooks

- Family letters

- Oral testimony and family stories

- All pedigrees, family histories, memoirs, articles and research reports

- All online trees!

While I have tried to illustrate each source type with a good range of examples, it can sometimes be challenging to definitively categorise some sources. A family bible, for example, might have the attributes of an original record in the hands of an assiduous recorder; in the hands of a less disciplined recorder, however, it might be derivative or even, authored.

A key point to consider is that authored works should point to the sources, whether original or derivative, they used to draw their conclusions, and derivative sources should point to the original source from which the data was abstracted/transcribed/indexed/translated etc. The genealogist should use this signposting to find a source as close to the original as possible so that they can assess it for themselves.

There is an implicit warning here – if the authored or derivative source fails to adequately identify the original source(s) then the researcher should hesitate to use it. The more one uses original records, the more reliable one’s evidence will be and the more convincing one’s conclusions. The strongest genealogical proofs often rely (almost) entirely upon original records.

Extracting and Classifying Information

Once the source – the container – has been categorised, one can extract and classify the information within it.

We all know that many of the records we rely upon contain multiple items of information. The step of unpacking the different information items, rather than considering the source as a monolithic whole, is key to understanding the reliability of each element and therefore the weights we can apply to them in our analysis.

Once each item has been extracted it is classified as one of three types:

- Primary – first hand

- Secondary – second hand

- Undetermined

At first sight this appears straightforward. But how do we decide if the information provided was given first hand or second hand? For this we need some knowledge of the record type under discussion, how the information was collected and under what circumstances.

How do we treat primary, secondary and undetermined information? A simple rule of thumb is that you can have more confidence in primary information that secondary information. Secondary information should always be corroborated before it can be used with a high level of confidence.

I will illustrate this with a couple of worked examples.

Example 1: Death Certificate of James Isherwood, 1860

This example would, under the old classification, be given the label of “Primary source.”

Image from certified copy in possession of the author.

We can extract the information items using a simple table:

Although it is a certified copy from the original register office, the (over) helpful staff have transcribed the original certificate rather than providing an image of the original, which would’ve been my preference. The document is therefore derivative.

Assessing the individual information items, we can say that any information supplied by the registrar is primary (first hand). Information provided by the informant is both primary and secondary (second hand). We know that the informant, Daniel Isherwood, was present at the death, so details of the date and place of death are primary. Equally, information provided by the informant about himself is primary. However, information about age and occupation of the deceased are most likely to be secondary. How do we know whether Daniel knew for sure that the deceased was 62 years old and a master shoemaker? The cause of death, we are told, is certified, so that must have been provided in writing by a doctor and handed to the registrar, who transcribed it, so this too is primary.

It is only by consulting other sources that I can make further assessment of the reliability of the secondary information provided by Daniel. From these I know that Daniel was in fact the eldest son of James Isherwood and a shoemaker, having been apprenticed under his father. So, by cross-referencing I can upgrade the statement of James’s occupation from secondary to primary. The stated age at death did in fact turn out to be correct as James died less than two weeks after his sixty-second birthday. But whether James ever celebrated his birthday and whether Daniel was ever aware of the date of his father’s birth remain unknown, so I still cannot upgrade that information item from secondary.

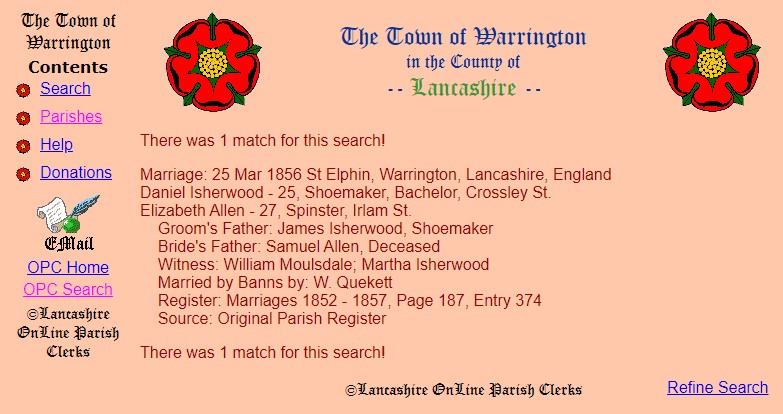

Example 2: Transcript of marriage of Daniel Isherwood and Elizabeth Allen, 1856

This example would, under the old classification, be given the label “Secondary source.”

Four years before the death of James Isherwood, his son Daniel married at St Elphin’s church in Warrington, Lancashire. It is a curse and a blessing with a town like Warrington which straddled a county boundary that some events of the Isherwood family took place just to the south of the town in Cheshire whilst others took place in the main town itself, which was in Lancashire. While images of parish registers are widely available for Cheshire events, those taking place in Lancashire are less well supported by good quality online images. However, there is a thriving and important Online Parish Clerks project for Lancashire, which has excellent coverage for Warrington (http://www.lan-opc.org.uk/).

A quick search of the Lancashire Online Parish Clerk site returns a transcript of the marriage register entry for Daniel and Elizabeth:

As before, we can extract the information using a simple table:

The source is a transcript and is therefore categorised as derivative. The information items would have been contributed by no fewer than five different people: the parish clerk, the groom, the bride and two witnesses. The clerk’s information is all primary, the bride and groom’s information given about themselves is primary, as are the declared names of the witnesses. But when the bride and groom supplied information about their fathers, this was secondary (second hand).

By cross referencing with other sources, including the death certificate of James Isherwood above, I am quite sure that the information provided about the groom’s father is entirely correct. However, despite years of searching, I have yet to find a convincing match in the right time window for the birth or baptism of an Elizabeth Allen to a father named Samuel Allen. I suspect therefore that this secondary information may in fact be technically described as a “lie”. My as yet unproven hypothesis is that the name Samuel Allen is most likely an invention – Elizabeth may well have been illegitimate and, like so many similar young women, simply didn’t want to admit to it in church on her wedding day.

[Aside: allowing for this being a transcription of the original, I later ordered a copy of the original marriage certificate to make sure that the details of the bride’s father had been captured correctly by Lancashire OPC. They had.]

Conclusion

Simply applying a single label to a source of “primary”, “secondary” and “tertiary” is fine for a historian who is dealing with historic events at the macro scale. But for the family historian, dealing with history on the micro, personal level, it is not enough.

One must separately assess the source – the container of information – and then each individual information item within it to consider who contributed it, under what circumstances, to whom, classifying each item separately as primary, secondary or undetermined. Primary information is of higher quality and requires less corroboration than secondary or undetermined information.

I hope you found this article useful. Please let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

Sources

- Elizabeth Shown Mills, A Template for Evaluating Evidence, Genealogical Computing 24 (Apr-June 2004), https://www.historicpathways.com/download/templateforee.pdf

- Genealogy Standards, Board for Certification of Genealogists (Washington DC, Second Edition 2019).

- Elizabeth Shown Mills Ed., Professional Genealogy, Genealogical Publishing Company (Baltimore, Maryland, 2018).

Fabulous post!

LikeLike

This is very helpful! I’m definitely adding it to the genealogy toolbox on my website…do you mind if I screencap your extraction tables as an example? I often do direct transcriptions, but those can be labour intensive and I realize an extraction form might be easier. I like the format you’ve used.

LikeLike

Be my guest. Please include a citation if you publish it elsewhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I definitely won’t republish, just include the link in my toolbox and likely refer to it in a coming blog post – I will cite it then 🙂 Thanks!

LikeLike

Another fantastic article Phil, and one which I’ve included in article this week whilst discussing the interpretation of curated diary collections!

LikeLike

Thanks Sophie. Look forward to reading your new article.

LikeLike

These 2020 blogs on the GPS elements are fantastic! So clear! Thank you.

LikeLike